Anime is a mainstream form of entertainment throughout the world today. The word “anime” likely even evokes a distinguishable style of drawing, allegorical storytelling, or fantastical settings. Maybe the ideas of monsters, martial arts, or giant robots come to mind. Anime hit the western world like a tidal wave in the 90s, and its popularity never faded. As a teenager in this decade, I not only had my mind blown by what seemed like an evolutionary shift in animation, but I saw the typical resentment directed at something new. In this two-part M.Y.O.P.I.A., I’ll briefly summarize the history of anime and how I never could have guessed this style of animated storytelling was here to stay.

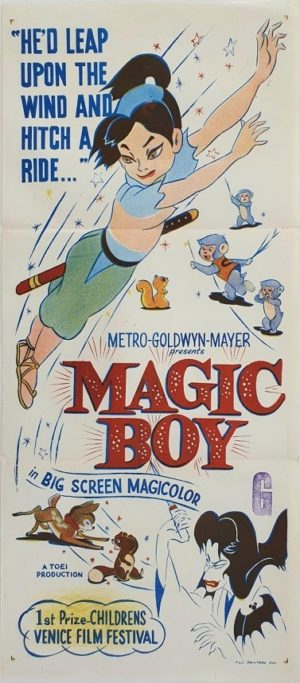

To try and summarize a deep history, animation began in the early 20th century (France, 1908). Japan quickly began to experiment with the medium and soon enough, produced some short films. Short films evolved into full-length movies by the mid-century. When television spread in the 50s and 60s, animation tended more toward quantity over quality. Think of how shows like Speed Racer and Astro Boy had nothing but lips moving when characters spoke. Since animation can often have universal appeal once translated, the idea of exchanging movies and shows became obvious. The first Japanese full length animated movie in US theaters dates all the way back to 1961 with Magic Boy.

Before going further, I need to mention manga. Similar to comic books, manga was largely influenced by the comics US soldiers brought over after WWII. Japanese culture quickly took to the medium and many ensuing cartoons were adapted from the popular printed stories. In fact during these early decades, animated cartoons in Japan were often referred to as TV Manga. The popularity of manga helped create solidarity with fans too. Various anthology magazines created a basis for news, for recognition of animators and cartoonists. Essentially, the connection between manga and animation, between fans and creators, it helped foster a culture different than in the US.

Sure, some western cartoonists experimented, but cartoons aimed at adults were largely met with skepticism in the west. US. Cartoons especially, were typically regarded as belonging to children. This was true for the Saturday morning cartoons over the next decades, true for most animated theatrical movies, and even largely true for early cartoons that crossed into primetime, like The Flintstones and The Jetsons.

In Japan, animation crossed over to primetime in the 60s as well. As various studios rose up, the push for quantity over quality reversed. Animators began trying to create better looking cartoons that told deeper stories, and experimentation began. In fact, some risqué animated shows appeared on late night TV. By the turn of the decade, shows aimed at a broader audience than children had caught on. For example, Attack Number 1 was about a women’s volleyball team competing in the ’64 Olympics. Tomorrow’s Joe was about a boxer’s career, and Lupin III was about a master thief and his criminal friends.

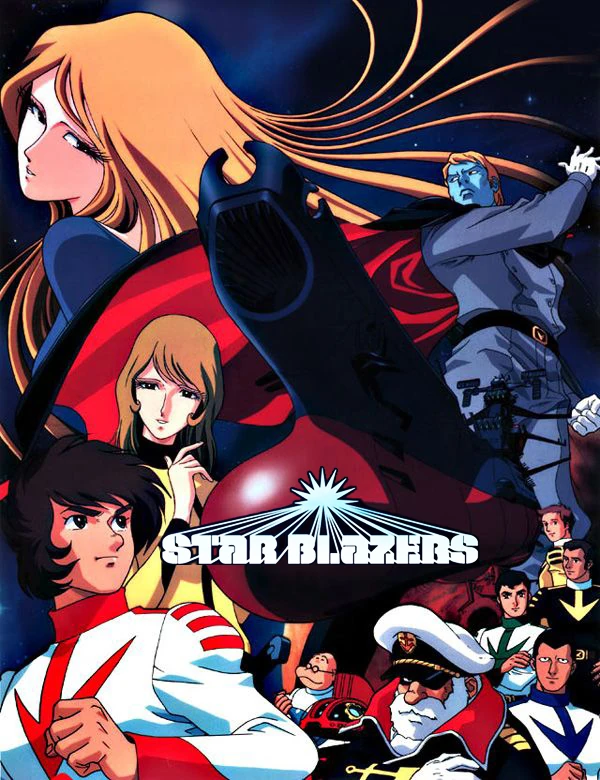

By the early 70s, Japanese animation had broadened to include science fiction, fantasy, and even the horror-genre. A show called Space Battleship Yamato from 1974 featured story arcs that required watching episodes in order. Main characters even died in this series. The show was partly noteworthy as one of the more mature themed animations eventually brought to the US, done so in 1979 as Star Blazers, although also heavily censored here. As the 70s pressed on, Japanese animators continued to push animation into new directions. Of course, on a global scale, entertainment was heavily skewed toward an interest in space. Star Wars came out in ’77, and the arcade release of Space Invaders in ’78 dominated in Japan.

I must admit that I expected to find an evolutionary film that shifted the Japanese market into pushing animated movies to catch on with all adults. Something that was always wildly different about Japan though, animation there was never really seen as something exclusive to young audiences. Even early theatrical animated shorts often revolved around adult themes. As TV cartoons had proven, animated shows were popular enough to primarily appeal to adult viewers also. Shows like Lupin III, and Space Battleship Yamato were even reworked into movies.

But if there was not necessarily a lynch-pin movie, but one that checked all boxes for things previously mentioned, it would have to be Mobile Suit Gundam. The movie was about a space war, about giant mechanized suits, and a rebellion fighting against overwhelming odds. Started as a TV series in the late 70s, paired with the fandom built around model kits for the Gundam mechs, the trilogy of Mobile Suit Gundam movies came out in the early 80s. The financial and cultural success of Mobile Suit Gundam was considered a turning point for Japanese animation. Japanese animation blew up in the 80s. Animated movie releases became more frequent, anime TV shows began some long legacies, and topics broadened as the genre gained immense acceptance as a signature part of Japanese culture. Of course, as anime began a revolution on animation in Japan, the rest of world was still a few steps behind. To leave off with part 1 though, I have to mention a pretty pivotal moment.

The word “anime” was not found in print until the year of 1985. Nowadays, the word has become all-encompassing, often used worldwide to refer to all Japanese animation. Even in Japan, the alteration of the English word, animeshon, caught on and is widely used there today. As movies proved lucrative and the world took greater of Japan’s animation, the word anime seemed like a perfect distinction for the unique style. But before anime became the largely accepted form of entertainment, there were a few barriers left in the way.