Ninjas are pretty much everywhere in popular American culture. They are widespread as both villains and heroes. They’ve appeared in movies, videogames, comics, and TV. The iconic ninja can appear on nearly any piece of merchandise, from pencils to pillows, and no Halloween would be complete without several ninja costumes on kids. We like ninjas in America, and even the very word, “Ninja,” probably can’t help but cause one to smile. So it’s only natural that the rest of the world, especially Japan, has a similar cultural obsession with ninjas right? Not really, actually.

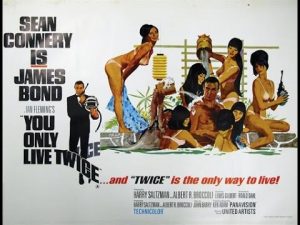

The ninja invasion of America didn’t even technically come directly from Japan. It actually came from  England, packaged with one of their most popular icons, James Bond. You Only Live Twice heavily featured Japanese culture, and ninjas were a pivotal part of the story. The book came out in ’64, and the movie in ’67, and these also came out at a time when the western world was ripe for such an interest. The 1964 Tokyo Olympics had sparked an interest in Japanese culture, especially martial arts, which were for the first time featured in the games that year. By the 60s, samurai movies were trickling out of Japan, and martial arts dojos were popping up in the US. The ninja thus, hit the ground silently running…and some misconceptions were also born.

England, packaged with one of their most popular icons, James Bond. You Only Live Twice heavily featured Japanese culture, and ninjas were a pivotal part of the story. The book came out in ’64, and the movie in ’67, and these also came out at a time when the western world was ripe for such an interest. The 1964 Tokyo Olympics had sparked an interest in Japanese culture, especially martial arts, which were for the first time featured in the games that year. By the 60s, samurai movies were trickling out of Japan, and martial arts dojos were popping up in the US. The ninja thus, hit the ground silently running…and some misconceptions were also born.

First up, the word ninja is mostly synonymous with Shinobi. The Japanese language has formal and informal terminology. Shinobi is the more formal word to describe the ancient clan of fighters. Japan nowadays more often uses the informal “ninja” to describe the westernized version of this traditional warrior. Historically, the Shinobi once rivaled the samurai in size and influence. As a samurai counterpart, ninja are sometimes naturally turned into villains, but this stems from other misconceptions.

First of all, the Shinobi were not simply assassins. Ninja fighting techniques arose because small villages needed a way to contend with soldiers, samurai, and corrupt politicians. Villagers with no armor and little access to weapons soon saw the value of stealth. Common folk developed ways to fight over many years, and gradually the best training areas became more centralized, hence the focus of the Shinobi clan. But ninja were not

First of all, the Shinobi were not simply assassins. Ninja fighting techniques arose because small villages needed a way to contend with soldiers, samurai, and corrupt politicians. Villagers with no armor and little access to weapons soon saw the value of stealth. Common folk developed ways to fight over many years, and gradually the best training areas became more centralized, hence the focus of the Shinobi clan. But ninja were not simply fighters. They were often master’s of disguise, and they were very good at gathering information. For example, ninja dressed as things like merchants and covertly counted soldiers while visiting a castle. Information might be sold to a rival, or was more likely used to protect the common folk. If need be, someone who posed a threat to peace might be killed because snuffing out one problem was easier than villagers meeting soldiers on a battlefield.

simply fighters. They were often master’s of disguise, and they were very good at gathering information. For example, ninja dressed as things like merchants and covertly counted soldiers while visiting a castle. Information might be sold to a rival, or was more likely used to protect the common folk. If need be, someone who posed a threat to peace might be killed because snuffing out one problem was easier than villagers meeting soldiers on a battlefield.

As ninja faded through history, some lore was born. Ninja became part of folktales, and were given superpowers: invisibility, walking on water, splitting into multiple selves. This lore was interspersed with entertainment, and by the early twentieth century, Japanese novels sometimes featured ninjas. Movies with ninja date back to the silent-era for Japanese films. But ninja were never necessarily a fad-like obsession in Japan. They seemed more a fact of history. And this leads to the 60s, when the idea of the ninja began to spread overseas.

A few years after James Bond, ninjas began to creep up in American entertainment in things like pulp novels and comic books. Most of these ninja were little more than a stereotype. For example, Iron Fist comics in 1975 featured a villain simply named, “The Ninja.” Luckily, some of Japan’s ninja movies trickled over, and kung-fu films like Shaolin vs. Ninja were dubbed into English. Still, domestic 70s films that featured ninjas, like American Killer Elite from ’75, were usually low-budget, overlooked exploitation films. Of course, one other factor to consider of the 70s was Bruce Lee. He never played a ninja, but Bruce Lee films were helping to widely popularize martial arts in the 70s, and this was helping to set a stage for a decade when ninja fit into pop culture like a grappling hook on a roof ledge.

A few years after James Bond, ninjas began to creep up in American entertainment in things like pulp novels and comic books. Most of these ninja were little more than a stereotype. For example, Iron Fist comics in 1975 featured a villain simply named, “The Ninja.” Luckily, some of Japan’s ninja movies trickled over, and kung-fu films like Shaolin vs. Ninja were dubbed into English. Still, domestic 70s films that featured ninjas, like American Killer Elite from ’75, were usually low-budget, overlooked exploitation films. Of course, one other factor to consider of the 70s was Bruce Lee. He never played a ninja, but Bruce Lee films were helping to widely popularize martial arts in the 70s, and this was helping to set a stage for a decade when ninja fit into pop culture like a grappling hook on a roof ledge.

The 80s loved ninjas. In 1981, the first centrally focused American ninja movie came out and was aptly named…Enter the Ninja. The movie was good, at least good enough to spawn sequels and copycats, like one of the other notable American ninja franchises of the decade, American Ninja (I swear I am not making these titles up). TV in the early 80s actually featured ninjas too. Of note, The Last Ninja, and The Master were both fairly short-lived, and were full of fairly uninspired scripts and fight scenes.

The 80s loved ninjas. In 1981, the first centrally focused American ninja movie came out and was aptly named…Enter the Ninja. The movie was good, at least good enough to spawn sequels and copycats, like one of the other notable American ninja franchises of the decade, American Ninja (I swear I am not making these titles up). TV in the early 80s actually featured ninjas too. Of note, The Last Ninja, and The Master were both fairly short-lived, and were full of fairly uninspired scripts and fight scenes.

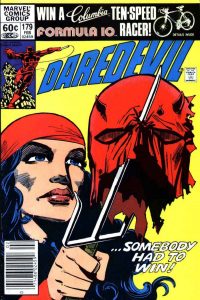

Comic books had been quick to absorb ninjas, and though some characters had appeared prior, 1980’s Elektra was the first ninja with deep character development. Wolverine soon had a history of bad blood with ninjas. DC’s League of Assassins soon absorbed traits of the ninja also. Toy lines got in on the flying shuriken action. The GI Joe line in 1982 featured Snake Eyes—seemingly a ninja, and partly created because it was cheap to manufacture a figure that didn’t need paint or much detail. Still, GI Joe toys, cartoons, and comics soon added other ninja characters. Videogames also seemed a very natural home for ninja. Though they were featured in games prior, the first American game, Ninja Warrior, came out in ‘83 for home computers.

Comic books had been quick to absorb ninjas, and though some characters had appeared prior, 1980’s Elektra was the first ninja with deep character development. Wolverine soon had a history of bad blood with ninjas. DC’s League of Assassins soon absorbed traits of the ninja also. Toy lines got in on the flying shuriken action. The GI Joe line in 1982 featured Snake Eyes—seemingly a ninja, and partly created because it was cheap to manufacture a figure that didn’t need paint or much detail. Still, GI Joe toys, cartoons, and comics soon added other ninja characters. Videogames also seemed a very natural home for ninja. Though they were featured in games prior, the first American game, Ninja Warrior, came out in ‘83 for home computers.

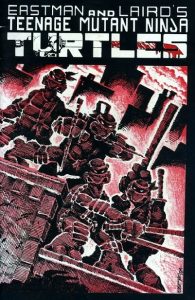

One of the most mainstream phenomena that probably helped many future generat ions and parents alike learn about ninjas, came in the form of turtles. The Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtle comic debuted in ’84, to a very small print run no less. By ’87, the cartoon and toy line were already snowballing into something bigger. It was the late 80s that really saw many different incarnations of ninjas. For videogames, Shinobi came out in ’87, and Ninja Gaiden in ‘88. Around this same time, ninja were also used as a generic sort of ploy to add twists to other games, like the forgotten BMX Ninja, or Ninja Scooter Simulator (really). Ninja were an easy stock choice for merchandising on clothes and toys and such since a generic ninja didn’t require any licensing.

ions and parents alike learn about ninjas, came in the form of turtles. The Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtle comic debuted in ’84, to a very small print run no less. By ’87, the cartoon and toy line were already snowballing into something bigger. It was the late 80s that really saw many different incarnations of ninjas. For videogames, Shinobi came out in ’87, and Ninja Gaiden in ‘88. Around this same time, ninja were also used as a generic sort of ploy to add twists to other games, like the forgotten BMX Ninja, or Ninja Scooter Simulator (really). Ninja were an easy stock choice for merchandising on clothes and toys and such since a generic ninja didn’t require any licensing.

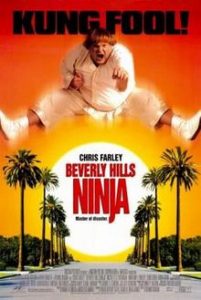

By the 90s, the commonality of ninjas was beginning to gear them to a less serious side. The Ninja Turtles  had a movie in 1990, but their popularity began to decline and other ninja movies popped up in a puff of smoke. In ‘92, Three Ninjas reduced the discipline of a ninja to something children could master. The next year, Surf Ninjas brought ninjas to the beach, yep, a ninja beach party. The trend of ninjas in our culture wouldn’t have been complete without an all out parody. In ‘97, Beverly Hills Ninja preyed upon all the silly ninja stereotypes.

had a movie in 1990, but their popularity began to decline and other ninja movies popped up in a puff of smoke. In ‘92, Three Ninjas reduced the discipline of a ninja to something children could master. The next year, Surf Ninjas brought ninjas to the beach, yep, a ninja beach party. The trend of ninjas in our culture wouldn’t have been complete without an all out parody. In ‘97, Beverly Hills Ninja preyed upon all the silly ninja stereotypes.

By the 90s, ninja just became so common that they were pivotal to American pop-culture. One couldn’t go far on Halloween without seeing a cheap sword and a black costume with sneakers pointing out. Ninjas continued to be parts of toys, comics, videogames and movies. Popular franchises have come and gone in waves, with some notably good exceptions. Movies have mostly been relegated back to the B-genre, but there are still some very good foreign ninja films made today. Ninja are just sprinkled throughout our pop-culture, from internet videos to phone apps. The word ninja is even applied to other titles: like ninja-chef, or ninja-marketer.

Unfortunately, some stereotypes about ninjas persist as common knowledge. The ninja were about so much more than fighting and killing. They were defenders of the common folk. They favored strategy and informative thinking. They were such masters at what they did that they became legends.

Perhaps it is then fitting that ninja are so common today. Perhaps it is fitting that there is a generic gloss to them, even to the very term “ninja” itself. They were masters of disguise after all, and with them everywhere, could it be possible that ninja are just continuing to do what they have always done best: hiding in plain sight.